On May 23rd and 24th the Nautical Institute organised an event in Malta to gather maritime experts and professionals to improve operations at sea. The agenda included good maritime practices for those working in this field who have to deal with migrants’ and refugees’ boats, as well as possible ways to increase the current level of vessels’ automation. Special attention was devoted to technology and its positive role in the SAR field if used to save the highest number of human lives. Since its inception, MOAS invested in a positive use of technology, by using S-100 Schiebel Camcopter drones that are usually deployed for military purposes. MOAS used them to expand our SAR area for many miles, to have a clearer overview of the situation at sea in order to inform the Italian Coast Guard and shorten delays in rescues.

Between August 2014 and April 2017 we operated drones, before later replacing them with a maritime patrol aircraft possessing the same technology. Drones helped MOAS’ crew to expand our capability in identifying vessels in distress and allowing us to rescue people who could have drowned without being spotted.

I found the presentation of Ann Fenech, a maritime lawyer, very interesting. On behalf of the law firm Fenech & Fenech, she addressed the innovative topic of vessels’ automation from a legal perspective to understand challenges and feasibility of a total or partial automation of the vessels at sea. My question was: what would happen if automated vessels without crew or master on board met vessels carrying migrants and refugees in distress? What would happen if the radar didn’t spot them in time to react, as it usually happens with dinghies that are often invisible to the equipment on board? Carl Hunter (AFNI, CEO, Coltraco Ultrasonics), who chaired the first session highlighted that automation is still an ongoing process because there are many aspects to clarify and improve. On different occasions, speakers recalled the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS).

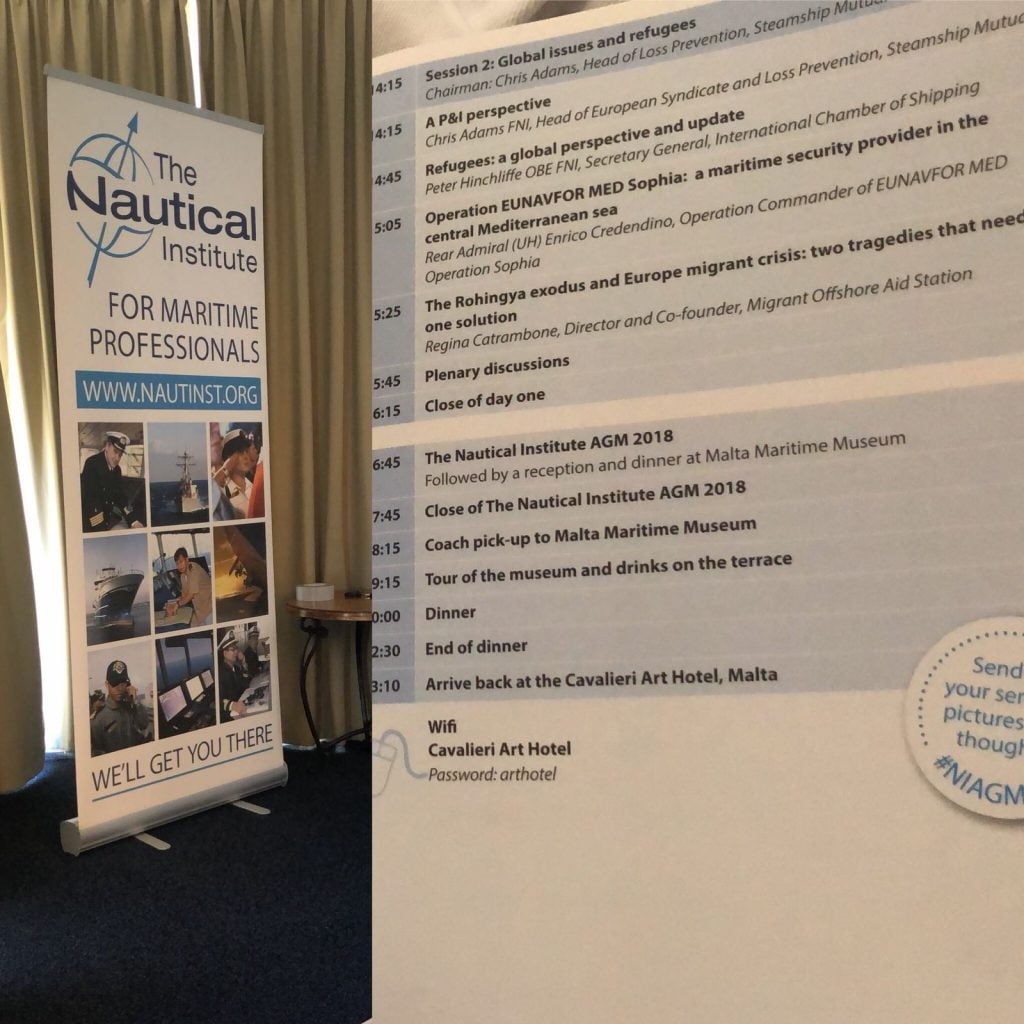

The afternoon session concerned migrants and refugees travelling in unsafe boats along the same routes as merchant ships. The main focus was insurance and liability of merchant ships if confronted with wooden boats or dinghies in distress, as well as the possibility that migrants climb to get on board these vessels without being spotted by the crew. It is important to mention that before MOAS’ creation, upon request and under coordination of the Italian Coast Guard, many rescues were carried out by merchant ships which are not suitable for this purpose both because of their structure and crew capacity and know-how. Today, Operation Sophia – EUNAV FOR MED plays a crucial role. However, in my view, everybody’s attention is focused on border defense rather than on unconditionally saving people in distress.

Peter Hinchliffe (OBE FNI, Secretary General International Chamber of Shipping) displayed a video showing SAR best practices for merchant ships in order to improve the way they react. Nevertheless, even though all attempts to improve the way merchant ships react to SAR needs are positively welcome, the real aim should be to rescue human lives and stop casualties along the world’s most dangerous migration route. The Mediterranean Sea is Europe’s doorstep, but Europe is not able to stick to its founding principles anymore. Those principles should be the starting point of Europe’s actions.

Thanks to Rear Admiral Enrico Credendino (Operation Commander of EUNAVFOR MED), the discussion involved Libya and how the Libyan Coast Guard is more and more active at sea. Additionally, IOM and UNHCR have consolidated their presence in some disembarkation ports where migrants are brought back after being intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard. Their presence on the one hand surely mitigates the suffering of those returned to Libya, but on the other hand corroborates such a situation. In my view, if we care about human dignity and rights, it is unacceptable to consider Libya a safe port since those who arrive in Italy talk about unspeakable violence. Moreover, Libya has never signed the Geneva Convention relating to the Refugee Status, a milestone to define refugees’ status and rights.

At the end of the session, as MOAS’ representative, I tried to give voice to the thousands of people rescued and assisted throughout three years of missions at sea, when we prevented the death toll from increasing along the Central Mediterranean and Aegean route. Also, I explained aims and results of MOAS’ latest observation mission in the Andaman Sea where we tried to better understand the SAR need in this area and explained how we are helping the Rohingya community in Bangladesh. Last October, one month after our arrival, we opened two primary health centres – called Aid Stations- where more than 60,000 children, women and men received medical assistance in just six months.

I do hope that this meeting is the starting point for future discussions. Dialogue, mutual understanding and cooperation to safeguard the most vulnerable are the only means to solve what we call “humanitarian crisis”, but is actually a “crisis of humanity”.