In July 2017, arrivals decreased by more than 50% compared to the same month in 2016. Nevertheless, people still talk about “being invaded” and limiting migration flows as much as possible. Apparently, nobody wants to explore the reason behind such an unexpected fall in figures despite good weather conditions and the very high number of people waiting to attempt the crossing and reach Europe. The United Nations have recently warned that in Libya around 800,000 people are currently stranded in degrading and inhuman conditions. Their only chance to leave Libya alive is to board an unseaworthy vessel, depending on smugglers who have turned the sea crossing into a lucrative and deadly business.

However, once again, the debate on current migration flows is focused on our safety and security, which are made to appear only possible at the expense of the safety of migrants and refugees who are entitled to receive protection pursuant to international law.

Those assisted by MOAS’ crew tell hellish stories, as confirmed by Mario Giro, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, and Vincent Cochetel, Special Envoy of the UNHCR for the Central Mediterranean situation. Ours guests on board the Phoenix are exhausted after journeys that leave marks both physically and emotionally. Nevertheless, they try to describe to us the abuse experienced in Libya where terror, beatings, violence –even sexual violence- and degrading treatment are a daily routine.

We have listened to tales of people trapped in warehouses and connecting houses where there is not enough air, water or food; where people are not even able to stretch their legs and are kept in prisons with no medical assistance, so that women deliver their babies alone, and those who die are just another number among thousands.

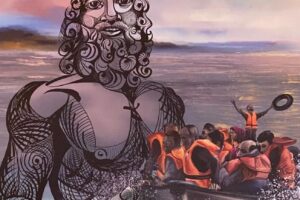

Each part of the journey is handled by a group of a larger smuggling network, and is a lottery where life is at stake. Then, the sea is in front of them: an immense blue surface, which many of them have never seen before. Now, the arduous sea crossing starts, and they hope that they will soon start a new life far from arbitrary violence.

In the eyes of the people assisted by the MOAS crew we can see their happiness at being safe, just when they felt hopeless. Our crew often has to manage and work in extremely precarious conditions with almost deflated dinghies, where people on board try to plug a leak with their hands or clothes. In the worst cases they find people already in the water. Nevertheless, in their eyes you can see a feeling of salvation.

If people do not arrive in Italy, what’s the fate awaiting them? What happens to them? What happens when they are intercepted by the Libyan Coast Guard, which takes them back to the place they were escaping from? Who is safeguarding their rights?

In light of MOAS’ mission and humanitarian commitment to saving human lives, these questions are crucial and we would like to have some answers, which are even more urgent since some migrant vessels have already been intercepted and brought back to Libya. Federico Soda, Director of the IOM Coordination Office for the Mediterranean, and Filippo Grandi, High Commissioner for Refugees, have denounced the lack of proper reception centres in Libya, and the presence of around 30 detention centres where people are jailed. In some cases, people sleep piled up on each other and are detained arbitrarily in a country devastated by deep political instability.

Instability is itself the main threat to a human and rational management of migration flows in Libya, which is a country of arrival, transit and departure, together with smugglers’ thriving business exploiting desperate people who should never fall in their hands. In our third anniversary since MOAS’ inception and one year after launching our campaign to open safe and legal routes allowing vulnerable people to reach European soil, it is crucial to find a solution to end the deadly sea crossings and revive hope in the eyes of those who look for a better life.