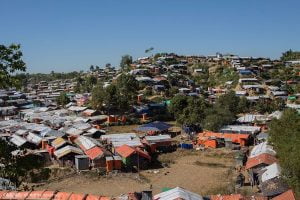

One year ago, MOAS opened the first Aid Station in Shamlapur, a fishing village in Cox’s Bazar, where Rohingya people would land after perilous sea crossings from Myanmar. Shamlapur was affected by the unparalleled exodus that led around 700,000 Rohingya to seek sanctuary in Bangladesh in the space of a couple of months. Additionally, arrivals have never really stopped, and between January and August 2018 at least 13,000 Rohingya arrivals were recorded in the country. This was not the first exodus in recent history, but it was certainlythe biggest one, and its consequences are devastating, as well as hard to predict.

The impact of our work on the field was immense and rewarded our efforts and energy to save lives. The MOAS team arrived in Bangladesh at the beginning of September, distributing food and humanitarian aid, while working unceasingly to build the MOAS primary health centres. The second Aid Station opened in Mid-November in Unchiprang.

One year later, MOAS medical teams in Bangladesh have treated more than 80,000 patients, with a monthly average of 7,000 visits that peaked in November 2017. The main conditions recorded were PUD (Peptic Ulcer Disease), respiratory diseases and conditions, pregnancies and maternal follow-up, or acute watery diarrhea. If we take into account the gender of our patients, among adults 63% are female, while the percentage of female children is 50%.

Children are at great risk in overcrowded and unsafe camps and settlements for many reasons. First of all, they are at great risk of child labour, trafficking and kidnapping, very vulnerable to marginalisation, isolation, lack of education and training opportunities when they become adults.

According to the Mid Term Review of Joint Response Plan, 10,900 children are at risk, including 6,013 unaccompanied and separated children who might have lost their families in traumatising situations or during the journey to reach Bangladesh. Children also make up almost half of our patients (44% as of the end of July), and among them 53% are aged between 2 and 17. But, there is also good news about children’s health. According to the Review, “Childhood immunization has over 89% coverage, while efforts are being made to reach out with vaccines to all children through routine immunization”, and good results were recorded also in the field of malnutrition, since the majority of the children treated recovered. MOAS volunteered its medical teams during two different vaccination rounds under the guidance of WHO and Bangladeshi government.

During my stays, I joined MOAS teams both inside and outside the Aid Stations; I walked around to visit some families or meet single mothers who survived rape and witnessed the killings of family members. I had the chance to talk to women whose infants or husbands were brutally murdered and still struggle to give a decent future to the rest of their family. I heard stories of young girls who were raped by armed officials and endured the journey to Bangladesh alone. So, based on my experience, I am concerned about the consequences of such an appalling situation and the tremendous lack of funds to cover all expenses.

One year later after our first visit in the MOAS Aid Station in Shamlapur, I am happy that we decided to keep hope alive for a historically persecuted minority that has been a major target of violence. I am proud that our primary health centres provided life-saving medicines and treatments for children, women and men who in some cases had never seen a doctor before.

In Bangladesh, there are currently only 33 primary health centres like our Aid Stations, each of them playing a vital role to assist both neglected Rohingya and local host communities, whose resources were under strain because of the effort to face such a massive exodus of desperate people in need of everything. The consequences of this are hard to predict entirely, but easy to imagine: more and more people will leave Bangladesh. A IOM report concerning the period between July and August documented that “migrants originating from Bangladesh represented the majority of Asian and Middle Eastern nationalities recorded (23,126 individuals representing up to 61% of Asian & Middle Eastern migrants identified)”.

How long can we continue to ignore that migration is a global issue?

I am not worried about the present, I am worried about the future. I am really worried that there will be no future for entire generations of children who might be condemned to a life of mere survival and exploitation, of girls who might be trapped in forced marriage and early marriage, of communities who will never thrive.

Migration is real, and it needs real and effective solutions, as well as a long-term vision that overcomes the principle of proximity that we are currently using to approach this issue.